A well-told love story, set against a background of religious orthodoxy

An important point to make from the outset is that Jewish law does not teach that it is forbidden to be a homosexual. On the contrary, Jewish law is concerned not with the source of a person's erotic urges nor with inner feelings, but with acts. The Torah forbids the homosexual act, known as mishkav zakhar, but has nothing to say about homosexuality as a state of being or a personal inclination.

In other words, traditionally, a person with a homosexual inclination can be an entirely observant Jew as long as he or she does not act out that inclination.

[...]

Lesbianism is never mentioned in the Torah. One talmudic passage refers to homosexual acts between women: "R. Huna taught, Women who have sex one with the other are forbidden to marry a Kohen." The Halakhah rejects Rav Huna's opinion and allows a lesbian to marry a Kohen. However, Maimonides ruled that lesbianism is still prohibited and should be punished by flagellation. The prohibition is not as stringent as that against male homosexuality because the Torah does not explicitly prohibit lesbianism, and because lesbianism does not involve the spilling of seed.

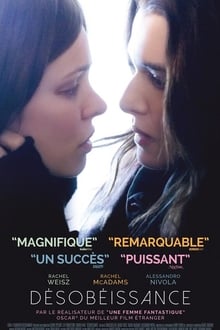

Depicting the problems that can arise when deeply held spiritual beliefs clash with notions of personal freedom, Disobedience is the story of a forbidden love given a second chance. Based on Naomi Alderman's 2006 novel, written for the screen by Rebecca Lenkiewicz (Ida) and Sebastián Lelio, and directed by Lelio, the film covers some of the same thematic territory as Lelio's previous features; Gloria (2013) deals with a 58-year-old divorcée trying to re-enter the dating scene by frequenting singles-bars, and the Oscar-winning Una mujer fantástica (2017) looks at a transgender waitress trying to come to terms with the death of her boyfriend, whilst also navigating a prejudiced society. In Disobedience, Lelio turns his attention towards a lesbian relationship within London's relatively insular Modern Orthodox Jewish community. What all three films have in common is the centrality of a complex and strong woman facing up to (almost exclusively patriarchal) societal hostility. Kind of like a cross between Todd Haynes's Carol (2015) and Daniel Kokotajlo's Apostasy (2017), Disobedience eschews melodrama, and is uninterested in presenting a binary story where faith is the Big Bad. Although it is certainly critical of the strictures that can result from a rigid application of Halacha [Jewish religious laws] and/or a literal interpretation of the Taryag Mitzvot [613 Commandments], the community itself is depicted respectfully, with the most representative Jewish character arguably the most sympathetic figure in the film. Disobedience does feature a very graphic lesbian sex scene, but it's one of the most thematically justified, least exploitative sex scenes I can remember, crystallising many of Lelio's thematic concerns. Although things can be far too on the nose from time to time, Lelio's subtle and non-intrusive direction more than compensates for that, and overall, this is a fine film, both thought-provoking and moving.

The story opens in a synagogue in London as Krushka (the great Anton Lesser), the local Rav, (similar to a rabbi, except an Halachic expert) delivers a sermon explaining that angels and demons are locked into their destinies, with only humanity "free to choose". This freedom, however, is both a privilege and a great burden, as it affords humanity the opportunity to disobey the edicts of HaShem [lit. "The Name"; used to refer to God when discussing Him outside scripture]. However, before completing his sermon, Krushka keels over and dies. Meanwhile, in New York, Ronit (Rachel Weisz), his estranged and non-practising daughter gets word of his death. After getting drunk and having anonymous sex with a man in a toilet, Ronit heads back to England. At the home of her childhood friend, Dovid Kuperman (an extraordinary Alessandro Nivola), Krushka's understudy, Ronit quickly learns the community is not especially pleased to see her, as the shadow under which she left has not dissipated. Despite this, and although he wasn't expecting her, Dovid is happy to let Ronit stay with him and his wife, who, Ronit is stunned to learn, is her former best friend, Esti (Rachel McAdams). The film then plays out over the next few days, as the community prepares for Krushka's levaya [funeral], as it becomes apparent that Ronit and Esti were once more than friends, which may, or may not, have had something to do with Ronit's departure and her estrangement from her father. However, the more time they spend in one another's company, the more their once-held passion for one another bubbles to the surface.

Thematically, Disobedience is far more concerned with the clash of views that results from Ronit's return than it is with condemning the beliefs of the community per se. When she first arrives at Dovid's house, she instinctively reaches out to hug him, forgetting about negiah [the forbidding of physical contact between men and women not related by blood, or married], and he immediately, although not unkindly, recoils. This tells us both how long she has been away, and how thoroughly she has rejected the doctrines of the faith. Later, there is an exceptionally awkward (but very funny) Shabbat [Jewish day of rest] meal, where Ronit seems to take great delight in being as outrageous as possible, riling up the assembled guests with her progressive worldview. In a discussion about the role of women in society, for example, she points out that every time a woman gets married and takes her husband's surname, a part of that woman's history is erased. This kind of ideological conflict, however, is also found within the characters themselves. Esti, for example, is torn between her desire for Ronit on the one hand, and her commitment to Dovid and her belief in their faith on the other. For her part, Ronit too internalises discord; although she has been estranged from him for many years, she is genuinely hurt to learn just how completely Krushka had divorced himself of her memory, seen most clearly when his obituary refers to him as "sadly childless".

Tellingly, during the Shabbat dinner, Dovid tries to play peacekeeper, whilst a couple of cutaways to Esti show her smiling to herself as Ronit burrows under the skin of those present. This kind of delicate touch on Lelio's part can be seen throughout the film, with numerous wordless gestures allowing the actors to convey backstory in lieu of exposition. For example, after Ronit arrives, although Dovid recoils when she tries to hug him, and although when she tries to light up a cigarette in his kitchen, he asks her to smoke in the garden, he accompanies her outside, shielding the flame from the wind in a gesture both kind and intimate. Another excellent example is found later that night as Dovid and Esti prepare for bed, and Esti gently and playfully strokes his beard, suggesting her genuine affection for him.

On paper, the story might lend itself to a condemnation of the kind of social suffocation and emotional repression that can result from fundamentalism. Instead, however, the film spends time building a respectful, if not idealised, picture of the community's beliefs and practices. Although no-one is especially happy that Ronit is back, they are never openly hostile, the way Hasidic Jews, for example, might be. A key part of this respect is Dovid himself, played by Nivola (in an Oscar-worthy career-best performance) as an inherently decent and honourable man; when Ronit returns, he is the only one to extend her a genuine welcome. In a less nuanced film, Dovid would be a fire-and-brimstone obstacle to Ronit and Esti's happiness, a Roger Chillingworth-type personification of traditionalism and rigidity. Instead he is presented as someone who, like Esti, faces a difficult choice – that between his communal position and his faith on the one hand, and his genuine love of Esti and affection for Ronit on the other, his lifelong devotion to the Tanakh [Hebrew Bible] conflicting with the modern day progressive sensibilities that come from living in a metropolis. Indeed, perhaps Dovid's most salient characteristic is conflict – when he tries to lay down the law to Esti regarding her conduct, his heart never seems in it; when he expresses disgust at her tryst with Ronit, he almost seems embarrassed to be reacting the way he is. This conflict is manifested aesthetically in a scene where Dovid is addressing the synagogue. Lelio films the scene in such a tight close-up, that every time Nivola moves even slightly off his mark, he goes out of focus. It's a brilliant example of content generating form, and is typical of Lelio's directorial lightness of touch.

However, for all that, the film never lets you forget that this is a community of negiah, where married women must wear a sheitel [wig] in public, and where the genders are strictly divided at religious services. As Ronit and Esti discuss their sexuality, Esti points out that she and Dovid have sex every Friday night, "as is expected", and that the reason she was married to Dovid in the first place was that Krushka hoped "marriage would cure" her, a concept not a million miles away from homosexual conversion therapy. In this sense, although respectful of the community, even depicting some of the communal benefits of such a tight-knit group, the film does challenge some of the tenets of their belief system, particularly its rigid traditionalism and myopic sexism, both of which feel increasingly out of place in the early 21st-century. In this, Disobedience fits very much into Lelio's oeuvre, with all three of his films dealing with repressive milieus placing restrictions on women.

Obviously, a major theme throughout is sexuality. Much has been made of the sex scene between Ronit and Esti, with some critics accusing it of being little more than titillation at best, a graphic example of the male gaze at worst. However, this reading is to completely miss the point of the scene in relation to the narrative as a whole. There are actually two sex scenes in the film; one between Ronit and Esti, and the other between Esti and Dovid. And although they couldn't be more different, they also couldn't exist without one another, as the abandonment, lust, and sense of pressure being released when Esti is with Ronit contrasts sharply with the detached, formulaic, and passionless scene with Dovid; the two scenes explicitly comment on one another, each hinting at the meaning to be found in its counterpart. In this, they recall the four sex scenes in David Cronenberg's A History of Violence (2005) and Abdellatif Kechiche's La Vie d'Adèle – Chapitres 1 & 2 (2013), two sets of two scenes which, again, comment upon and contextualise one another. The scene between Ronit and Esti is the physical manifestation of the characters' long-repressed desire for one another, a release of the yearning that has been building up for years. It's a wholly justified narrative moment, and a completely necessary beat for the two characters. It's not an aside or a piece of voyeuristic male fantasy, it's the centre of the whole film. Together, the two scenes represent Esti's binary choice – an unbridled and sexually fulfilling, but unstable relationship with Ronit, or a dutiful and dull, but respectful and secure relationship with Dovid.

If I had one major criticism, it would be that although Lelio's direction is extremely subtle, some of his and Lenkiewicz's writing choices are spectacularly on the nose. The opening sermon is a good example – a religious diatribe whose subject is mankind's freedom to choose, the concomitant ability to disobey, and the notion that freedom is impossible without sacrifice, in a film about these very same issues. Another example is that Dovid and his yeshiva students are discussing the one book of the Tanakh dealing with sexuality rather than spirituality, the Song of Songs, whilst Esti's secondary school students are studying adultery in Othello. The worst example of this, however, is found when Ronit and Esti go to Krushka's house and Ronit turns on the radio, which just so happens to be playing The Cure's "Lovesong", a song which perfectly encapsulates their situation ("Whenever I'm alone with you/You make me feel like I am home again"). It's not exactly subtle. I'm also not a massive fan of Matthew Herbert's score, with its jaunty use of woodwinds cutting against the ominous tone of the narrative.

These two issues aside though, this is an excellently crafted film. Once again examining female desire, issues of patriarchal oppression, and profound self-doubt, Lelio delivers a mature and considered meditation on the conflict between faith and sexuality. Eschewing the kinds of black and white criticism of secular isolationism as seen in films such as Sidney Lumet's A Stranger Among Us (1992) or Boaz Yakin's A Price Above Rubies (1998), Lelio respects the milieu too much to cast it as the villain. Instead, there is an elegance to the way in which he depicts it. Equal parts sensual and spiritual, the lethargic pace and absence of any narrative fireworks will probably alienate some, especially those expecting a pseudo-porn movie, but for the rest of us, this is thoughtful and provocative cinema in the best sense of the term.