A powerful and personalised indictment of church and state-sanctioned abuse in a country once run by the clergy

Is this a holy thing to see,

In a rich and fruitful land,

Babes reduced to misery,

Fed with cold and usurous hand?

It is impossible to exaggerate the good effect which has been produced in the reduction of juvenile crime by [the] twin system of Reformatory and Industrial Schools. The latter have been particularly successful in Ireland; and the combination of voluntary effort and private management, with State regulation and partial support - a rather dangerous experiment - has been completely justified by the result.

A casual labourer, Pat Rourke, Who hurried from bricking across the water

With wife and babes, could find no work here.

All slept in a coal-hole, heard

(When light, that dwindled through the grating,

Was Wicklowing from strand to hill)

The gulls, loop-lining, near Dublin Bay,

Squabble for offal, rub of cur

Or cat around a dustbin, till

A-bang in a breadshop, dairy. Brought

To Court, the little screaming boy

And girl were quickly, for the public good,

Committed to Industrial School.

The cost - three pounds a week for each:

Both safely held beyond the reach

Of mother, father. We destroy

Families, bereave the unemployed.

Pity and love are beyond our buoys.

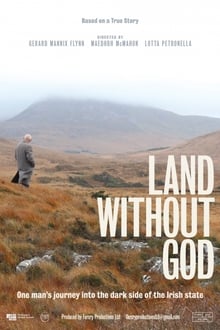

Land Without God, a harrowing documentary co-directed by Gerard Mannix Flynn (whose story the film tells), Maedhbh Mc Mahon, and Lotta Petronella, is an act of reclamation. It's a reclamation of the right to tell one's own story, a story of abuse and trauma, the malignant tendrils of which have spread to every corner of Ireland. There are very few people in this country over the age of 40 from working-class families who don't know someone who experienced the horrors of the Magdalene Laundries or the Industrial Schools. For me, it's an uncle who spent a year in St. Josephs Industrial School, Artane, one of the most notorious in the country. His crime? He smashed a window. He's 81 now, and has never spoken of his experiences in that place; whatever happened to him there, he will take to his grave. Almost all of us from working-class backgrounds have similar stories in our families. I mention specifically working-class families because poverty is one of the main themes of the film. Or rather, the exploitation of poverty, insofar as the Laundries and Schools provided what was essentially slave labour - a workforce plucked almost wholly from the working-class.

Flynn was born in 1957. His mother sold vegetables at a market stall whilst his father swept the streets. The 14-child family lived in a two-bed 'apartment' in Mercer House on Dublin's south side, with the parents too poor to send Flynn or his siblings to school. So they roamed the city, getting into mischief. And as the years went by, sibling after sibling would find themselves in court for some asinine misdemeanour (like stealing a dinky car or a box of chocolates), and would invariably be sent to one of the Schools, where they would be regularly beaten and raped. Austin Clarke had viciously condemned the Schools (and the church's hold over the Irish populace) as far back as the 1960s, but it was Flynn's 1983 novel Nothing to Say which offered one of the first eye-witness accounts of life behind closed doors. 1983 was a time when the Catholic Church still ruled Ireland, but in the next two decades, others would follow Flynn, culminating in 1999 with States of Fear, the Tomás O'Sullivan-researched and Mary Raftery-produced RTÉ documentary series about the abuse of children in the Schools. The series proved so explosive, it led to then-Taoiseach Bertie Ahern issuing a formal state-apology before the last episode had even aired. Since States of Fear and the publication of Raftery and O'Sullivan's Suffer the Little Children: The Inside Story of Ireland's Industrial Schools later that year, the Catholic Church's vice-like grip on Irish society has eroded almost to the point of non-existence, a process that has only picked up speed in the years since the 2009 publication of the findings of the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse, commonly known as the Ryan Report, a 10-year 2,600-page investigation into an industry built on abuse, neglect, and hypocrisy. Yet the removal of the church from its role as supreme moral authority in Ireland doesn't change the fact that so many innocents suffered for so long, it doesn't rewrite history. That history is the subject of the aptly-named Land Without God. And as much as it's an act of reclamation, so too is it a plea that we never allow that history to be forgotten – we owe the victims that much at least.

The film tells the story of Flynn's time in the Schools, how his siblings were damaged by their own experiences, and how the family has spent the last 50 years attempting to recover. However, because so many people have similar such stories, Flynn's story is very much a representative narrative. The film is an intimate family portrait, but it's a portrait which many will recognise as not dissimilar to their own. However, rather than functioning as an investigative piece or a catalogue of abuse, it is instead more anthropological, looking at how the majority of those sent to the Schools and Laundries were poor and how the working-class people of Ireland have yet been able to find peace. Why did this happen? How does one recover from such trauma? Why did the state do nothing? Unanswered and perhaps unanswerable questions that cast a shadow over Ireland which will take a very, very long time to dissipate.

With Flynn as interviewer, he speaks to his sisters Anne, Margaret, and Evelyn, his brothers Patrick and Bernard, his nephews Gary, Luigi, Clive, Ronaldo, and John, and his niece Anne as they recount (many for the first time) their separate but similar experiences. They make no bones about the fact that they were truants, but their story illustrates the shameful barbarity of how the state dealt with the impoverished even when they committed only the most minor of infractions. Not only that, but so too does it attest to the failure of a system wherein the Schools were ostensibly intended to be places of reform, as time spent there when children often led to addiction and prison in adulthood - reference is made to "the beast they placed in us", as the family speak to how they were far worse coming out than they were when they went in.

The theme of poverty runs throughout the film, with Flynn recalling the social stigma of being poor, recollecting, "we were branded" and asking, "is it a crime to be born poor?" There's real anger that the two most powerful bodies in Ireland at the time, the Catholic Church and Rialtas na hÉireann (Government of Ireland), targeted the most vulnerable and defenceless of people. However, poverty is important not only in terms of how the Schools housed children almost exclusively from poor backgrounds, but also the marginalisation of the working-class in later years, as Flynn points out those who were in the Schools tend to be thought of only in terms of victims and survivors, denied their own agency, rarely seen as the keepers of their own narratives ("our past did not happen"). At a Q&A with Flynn after a screening at the Irish Film Institute in Dublin, he stated that the film is an attempt to "put this history into the national discourse", whilst on the film's official website, he writes,

our story has always been stolen, sold and told by somebody else. We have been pitied rather than given justice. This film is told by those who witnessed, experienced and suffered the institutions first hand [...] I want this film to redresses the absence and silence and correct the historical record. This is an opportunity to ensure Ireland's history and our history is included and written by those who experienced the unthinkable and who live to this day with the unfixable.

Tied into this is Flynn's disgust with the Retention of Records Bill – a controversial bill proposed in February 2019 that proposes to seal the records of the Ryan Report and its associated bodies for 75 years, with a provision to renew the bill every 25 years. Currently, the National Archives Act, which the Retention Bill aims to bypass, provides for the withholding of records more than 30 years old only when the release of such records is deemed contrary to the public interest, constitute a breach of statutory duty, or contain information supplied in confidence that could cause danger to living persons. The Retention Bill would seal all records, not just those fulfilling the above rubric. In the documentary, Flynn declares, "they now want to lock up our testimonies for 75 years" (the records will be sealed even for those who provided evidence) in what he sees as another example of the working-class being denied ownership of their own history.

From an aesthetic point of view, the film is composed of two main elements - interviews with Flynn's family and footage of Flynn visiting the places of his youth and the Schools in which he was detained, now mainly derelict shells. This footage has a remarkably tactile component as Flynn is shown touching everything with which he comes into contact – running his hand along railings, peeling paint from walls, opening and closing doors, wiping dust off tables. The footage is usually accompanied by a poetic monologue written and spoken by Flynn, with the importance of memory in the voice-over cogently represented on screen, as if touching these places galvanises his recollection.

If I were to criticise anything, it would the short runtime of 74 minutes and the strange stylistic choice to intermittently feature Flynn in a room with a chalkboard, on which he writes the subject-matter about which he is going to speak. Obviously intended as chapter headings, it's the only formal affectation in the film, and it stands out as stylistically divorced from everything else, a more directorially manipulated element than the raw cinéma vérité-style filmmaking employed elsewhere.

This minor step notwithstanding, Land Without God is powerful stuff. People outside Ireland are far more likely to be familiar with the Magdalen Laundries than the less-documented Industrial Schools, and for that reason if nothing else, it's an extremely important film. Raw and honest, it's equal parts moving, infuriating, and harrowing. I don't imagine it'll find much of an audience in theatres, but it should have long legs beyond that, especially in education, where it'll be an invaluable primary source. It should also travel well, finding audiences keen to learn more about this black chapter in Irish history and the hypocrisy of a church who shielded its members as they preached morality in public whilst raping children in private.